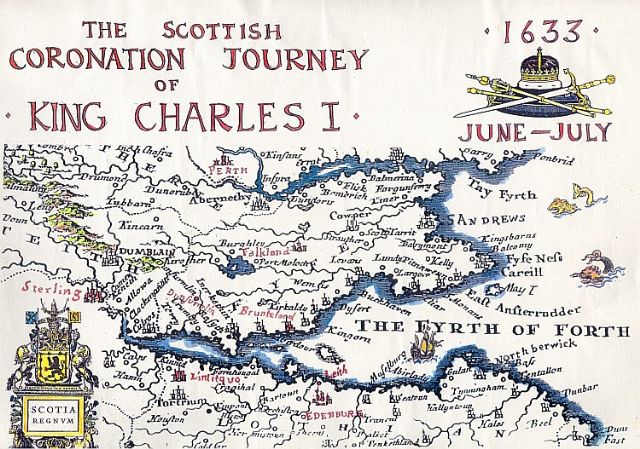

The Coronation Journey of King Charles I

and the Loss of the 'Blessing' (1633)

The Late Bob Brydon

The Coronation Journey

Bob Brydon's research and his discovery of the events of 1633

In the late 1970s, Robert (Bob) Brydon, a professional researcher and writer based in Edinburgh, began researching The Coronation journey of King Charles I in 1633, and related events in Scotland.

During his research, and while going over the little known and sparse records, he uncovered a calamity which had occurred and which was to prove politically embarrassing in the extreme - the loss of a ferry boat off Burntisland in that summer of 1633. Two Burntisland ferries had been chartered to carry the King and his baggage across the Forth, and his baggage ferry had foundered in a storm. The King himself had witnessed the accident and the loss of lives

As the drama of the ferry’s short voyage from its point of departure unfolded and the nature of the accident was revealed, it was obvious to Bob that this tragedy concealed a story of Royal lost treasure as yet untold. He also believed that, owing to strong political and state motives, any publicity regarding the affair had been vigorously discouraged by the King - in essence, a cover-up.

From what Bob had been able to ascertain and from the fragments of the story that came to light, it was also apparent that no recovery attempt had been made on the ferry and its cargo.

In 1993, he and his wife Lindsay published their booklet, "The Scottish Coronation Journey of King Charles I" - an account of what he had discovered in the preceding 15 or so years.

Bob Brydon died in Edinburgh in May 2014. His final words in a Discovery Channel documentary regarding the search for the lost vessel that he had helped get underway were “Oh, they’ll find it all right … they’ll find it … there’s no question about that … they’ll find it … when, is another matter” - and how prophetic he was!

Charles I

Charles I was born in Dunfermline Palace (pictured right) on 19th November 1600. He was the last British Monarch to be born in Scotland. He was a sickly child, unable to speak until the age of five. However, he outgrew his defects and became a skilled horseman and marksman, taking great pleasure in hunting. He was also an accomplished musician, scholar and student of theology.

Charles was the second son of King James VI of Scotland but after his father inherited the English throne in 1603, he moved to England where he spent much of the rest of his life. He became heir apparent to the English, Irish and Scottish thrones on the death of his elder brother, Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales, in 1612.

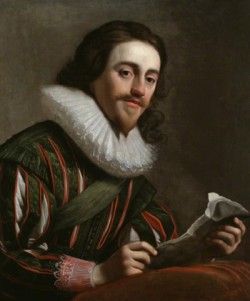

When his father King James VI and I died in 1625, Charles (pictured left, courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London) became the second king of the United Kingdom. Charles I's English Coronation ceremony was held in February 1626, and there was some debate as to whether or not there should be a separate Scottish Coronation. Although born in Dunfermline, Charles was not keen to visit the land of his birth. He even suggested that he might be crowned King of Scots in London. However, the Scottish Parliament insisted on a Coronation in Edinburgh.It took several years for matters to get to the stage where a date could be agreed. Eventually it was decided that the Scottish Coronation would be held on 18 June 1633 in the Abbey adjoining the Palace of Holyroodhouse.

Charles I entering Edinburgh

The Loss of the Ferry

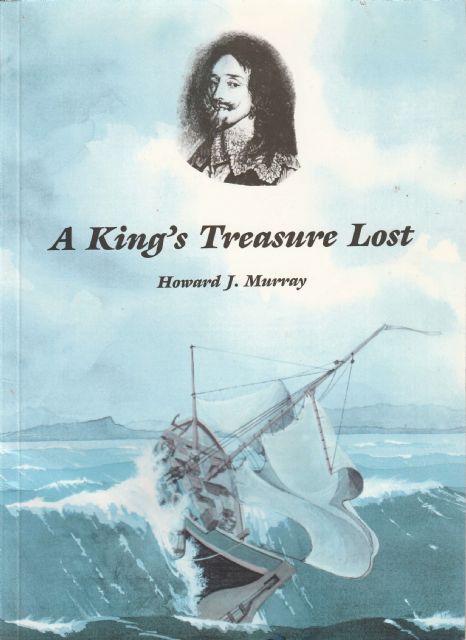

It has been suggested that the notable absence from the records of the tragedy which was to follow was the result of a cover up to protect the King from embarrassment. We therefore do not know exactly what happened on that fateful day. However, Robert Brydon and Howard Murray have independently researched the events, and the following account is based on their conclusions from the little information available.

It appears that two Burntisland ships had been chartered for the King and his priceless possessions. One was to carry the King to a naval ship anchored in Burntisland roads. Brydon suggest that this was a man o' war, the 'Dreadnought', which had sailed from London as part of the Coronation plans. Murray thinks that it is unlikely that it was the 'Dreadnought', but that it was simply a ship 'supplied by the Lord High Admiral, at least two masted and capable of carrying a large number of passengers'.

The Burntisland ship carrying the King (and perhaps under the command of Captain A. Watson) left first and made its rendezvous with the larger vessel offshore, with the transfer of the King and some of his personnel being effected without any problems. The King then set sail for Leith, probably followed by the Burntisland vessel from which he had transferred.

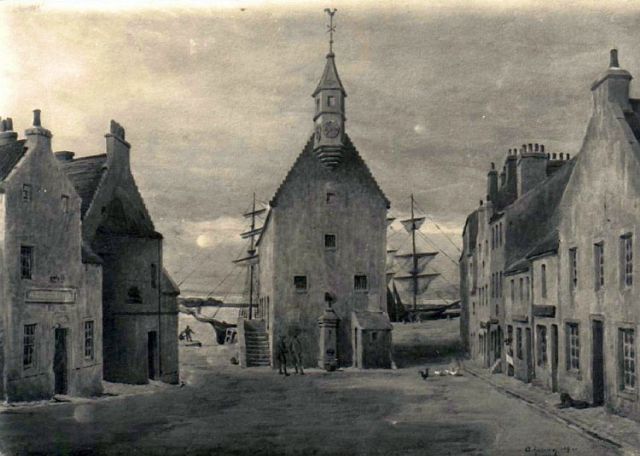

Burntisland's East Port as it might have looked in 1633; artist's impression by Keli Clark.

A contemporary account of events

The following is an extract from John Spalding’s contemporary account of the Scottish Coronation visit of King Charles I in 1633:

“Bot as he is on the water, in his awin sicht thair perishit ane boit following efter him, haueing within hir about 35 personis of English and Scotis, his owne domestik seruitouris, and tuo only escaipit with thair lyves. His Majesties siluer plait and household stuff perishit with the rest.

A pitiful sicht no doubt to the King and the haill beholders, whairof the like wes neuer sein ane boit to perish betuixt Brunt Island and Leith in ane fair symmeris day, but storme of wether, being the tent of July. Bot it foirtokint gryte trubles to fall in betuixt the King and his subiectis, as efter do appeir."

Spalding also offered perhaps the best and last pithy Scots comment: 'It is said his Majesty commendit our Scottish entertainment and brave behavior, albeit some lords grudgit with him.'

Another commentator puts it that the King himself 'was in grate jeopardy of his lyff.'

Kings Treasure Lost by Howard J. Murray ISBN-095351630X

The Tollbooth as it would have been seen by the King in 1633

The King and his vast entourage left London on the 10th of May, and arrived in Edinburgh five weeks later. The Privy Council had spent significant sums of money on upgrading the roads and bridges in advance of the journey. The noblemen with whom Charles stayed overnight during his journey had been ordered to ensure that their castles were, literally, fit for a King. And the same noblemen also had to feed and entertain him in the style to which he was accustomed. So great were the sums involved, that some of the nobles did not regain their financial equilibrium until years afterwards.

The same was true in Edinburgh, where no expenditure was spared. In return, the citizens were treated to a week of royal pageantry, with processions, royal banquets and a host of visiting foreign dignitaries; plus, of course, the Coronation itself.

Dunfermline Abbey birthplace of Charles I

.jpg)

by Eric Bell

In the meantime, the second Burntisland ship (the 'Blessing', which may have had Captain J. Orrock as master) set sail directly for Leith. No doubt heavily laden, she would have been less able to ride out the sudden squall which arose off Burntisland and which caused her to founder.

(Recent research has indicated that Captain Watson's ship, which carried the King, might have been the 'Blessing', and that it was Captain Orrock's (unnamed) ship which foundered. Further investigation is required.)

Howard Murray suggests that the two Burntisland vessels were between fifty and seventy feet in length and fifteen to twenty feet in breadth, with a carrying capacity of between 60 and 100 tons. They may have had the ability, as later boats had, of running cargo down a ramp into the hold.

Accounts of the tragedy give contradictory accounts of the number of lives lost. Murray estimated that the boat which sank was carrying some twenty to thirty people - a Burntisland crew of nine, with the remaining ten to twenty or so being servants of the King. There appear to have been only two survivors.

The original scheduled five day stay in Edinburgh was cancelled. On the morning of Friday 12th July, the distraught Monarch, his Court and Guards, departed posthaste for England to show the Royal face and dispel growing rumour that the King might be dead. Charles arrived at Greenwich on Saturday 20th July no doubt to be met by his anxious Queen, Henrietta.

Lindsay Brydon captures the King's incredulity when the ferry sinks.

Lindsay Brydon captures the King's incredulity when the ferry sinks.

The Aftermath of the Sinking

The bodies of two of those who perished were discovered. One was described as being found in Burntisland harbour and was identified as John Ferries, the King's cook. The other (unidentified) body may also have been found in the harbour. James Speed records what happened following the discovery of Ferries' body:

1633. It is recorded as follows [that at a Burntisland Town Council meeting held on 3 August 1633] 'The Bailies and Council considering that an John Ferries, servant to His Majesty, was found dead within this harbour and brought to land, who died in the boat betwixt this and Leith the time that the King His Majesty was upon the sea betwixt this and Leith, the tent day of July last; and there was found upon the said Jn Ferries the money and others following to wit, of dollars and other white money, forty five pund, twelve shillings; and of gold five twelve pund pieces and one single angel of gold 25 lib 8 shillings and 8 pennies .....

Item; ane ring of gold which was put in the council house.

Item; ane rapier sword with ane belt and hinger.

Item, ane coat and breeks of camblet.

The Bailies think meet that the sums bestowed on his burial be paid to the following persons, viz:-

To Andro Orrock for making graif, 16 shillings.

Item, to John White for ringing the bell, 16 shillings.

Item, to Janet Mair and Elspat Cousin for winding him, 13 shillings.

Item, to William Mitchell for washing his cot and breeks, 16 shillings.

Item, to James Brown, Taylour, 5 elns of linen to be his winding sheet, five pund, 8 shillings.

Item, to David Stirling for making his kist, 3 lib, 10 shillings.

Item, to the workmen for carrying him to the tollbooth and after to the kirk, 32 shillings.

Item, to Alexander Barnie for first spying him in the wold, 31 shillings.'

August 13. Ane dollar taken out of Mr Ferries' purse to pay for the winding sheet of other man found with him.

Sept 17. The Lord Admiral desired the money and other effects which belonged to Mr Ferries to be given up to him.

Dec 24. The affair of the late Mr Ferries, who it appears had been His Majesty's cook, after much negotiating was concluded by the Council obtaining, by what means is not known, the property found on him 'to be given to the Kirk Session, deducting alway 40 libs to be given to the Lord Admiral for his gude will in the said money, and the Council think it expedient that the minister and Session build ane seat round the pulpit for sick aged men of the council and Session as cannot well hear the minister's voice'.

Although John Ferries was described as the King's cook, this is slightly misleading. Given the amount of money he was carrying, and the elaborate funeral he was given, he would no doubt today be referred to as the King's head chef. He certainly held a senior position in the royal household.