Robert Kirke

(1815-94)

The story of Robert Kirke and his extended family is a fascinating one. It can be traced from their humble beginnings in Cairneyhill, near Dunfermline, to their position of power and influence in Burntisland. It encompasses the dark days of slavery in Suriname, a former Dutch colony on the tropical northeast coast of South America.

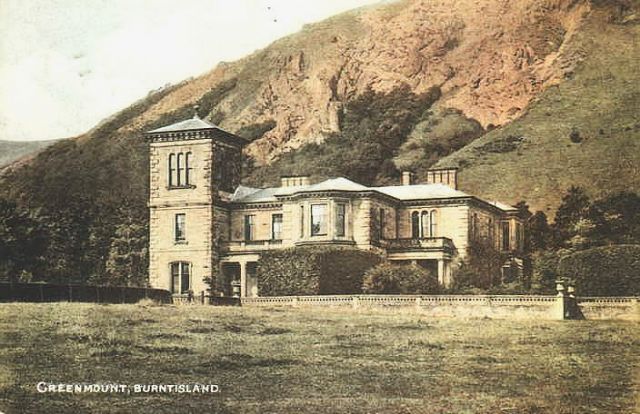

Greenmount House early 1900s

.jpg)

Philip Dikland, Suriname architect and historian

Philip Dikland, Suriname architect and historian, has recorded the remarkable influence of Scots as plantation owners and managers in Suriname in the 19th and early 20th centuries.The photograph above, shows a sugar press manufactured by the Harvey Engineering Co Ltd of Glasgow in 1906 and now lying abandoned on what was Robert Kirke's Hazard Estate. Photo courtesy of Philip Dikland. (Philip also appears in the photograph.)

In the early 1800s, Dr James Balfour, a miner's son from Dalgety, acquired slave plantations in the Nickerie district of Suriname. (More information on James Balfour can be found on the Slaves & Highlanders website.)

Back in Scotland in 1813, Balfour's sister Helen married a Cairneyhill weaver, Robert Kirke. Two of Robert and Helen's sons, Robert junior (a stonemason) and David, went to Suriname to work for their uncle, James Balfour. They showed promise and were soon actively involved in the management of the plantations. Balfour gave them great encouragement and identified Robert as a suitably talented relation to take over his plantations when he died.

Balfour never married. After he died in Suriname in 1841, the bulk of his estate did indeed pass to his nephew, Robert Kirke junior. Balfour also left a substantial inheritance to Harriet, his illegitimate daughter by a slave; and small ones to the sons of his disgraced brother, Thomas, who had been expelled from Suriname in 1824 for murdering a slave woman, probably his mistress, in a fit of jealous rage. Harriet had the rare distinction of being both a slave, and also a slave owner when she inherited a share of her father's estate.

The Balfour/Kirke link was strengthened when Harriet married Robert Kirke's second son, David.

Above (circa 1962) and below (circa 1940) - two rare photographs of the Waterloo sugar works and plantation in Suriname.

Photographs by the late Charles L.P. Pickering. Lilian Neede-Pickering collection.

Whether by happy coincidence or by design, the Kirke family had secured almost complete control of Balfour's Waterloo and Hazard plantations. However, David Kirke's branch of the family did not live to enjoy the fruits of their inheritance. David died in Suriname in 1850, aged 31; Harriet in Suriname in 1858, aged 40; and their three children in infancy, two at their Scottish family home at Culross and one in Suriname.

Robert Kirke junior married Janet Johnstone of Dunfermline in 1850, and their first child, Kate, was born in Suriname in 1851. By February 1852 he had decided to make his permanent home in Burntisland. It is likely that he set sail for Scotland a few months later, accompanied by his pregnant wife, his infant daughter Kate, his freed slave Petronella Hendrick, most of his possessions, and large quantities of Surinamese hardwood. He bought the estate to the north and east of Burntisland from the Youngs and started planning his great mansion house of Greenmount (see separate page for photos of Greenmount). At the same time, his wife's family, the Johnstones, were building Kingswood on the eastern outskirts of the town.

Kirke and his family stayed in rented houses in Cromwell Road and in Craigholm Crescent until Greenmount was ready for occupation about 1859, complete with its beautiful panelling created from Surinamese hardwood. Extensive grounds included an orchard and banks of greenhouses where grapes, nectarines, peaches, apricots, tomatoes, and figs were grown. The head gardener lived in the lodge at the bottom of the drive next to the stables and managed twelve gardeners.

.jpg)

Kirke now liked to think of himself as a gentleman farmer as well as a plantation owner, and he took a keen interest in his Greenmount Farm.

The family's new status required a change of name, and it was around 1860 that the simple Kirks became the more fashionable Kirkes.

Although now based in Burntisland, Robert Kirke retained tight strategic control of the Suriname operations, with the day to day running in the hands of trusted managers. The latest machinery from Glasgow and Falkirk was installed and by 1859 Kirke's main plantation, Waterloo, was the most modern in Suriname. Sugar was in great demand and Robert Kirke was making a fortune.

The end of the slave trade and the subsequent emancipation of the slaves in the Dutch colonies in 1863 (with a transition period to 1873) resulted in significant compensation being paid by the Dutch government to those who had owned slaves. From the UCL database:

"In 1863 the heirs of James Balfour were awarded 116,100 guilders for 387 enslaved people (the claim was for 392) on Pln. Berlin in Surinam. The awardees were Robert Kirk [sic] (then of Burnt Island) for 41/48ths; James Balfour and Thomas Balfour, both of Dunfermline, for 2/48ths each; and John Janet [sic] Duncanson for the remaining 3/48ths. The four individuals shared in the same proportions the 50,700 guilders in compensation for 169 enslaved people on Plantage Hazard on the River Nickerie in Surinam, the 1,200 guilders in compensation for 4 enslaved people on Plantage Lot No. 1, the 900 guilders for Plantage Lot K, both also on the River Nickerie, as well as 68,700 guilders for 229 (the claim was for 231) enslaved people on Pln. Waterloo, again on the River Nickerie."

The end of slavery also meant a shortage of labour on the Suriname plantations. Although the Kirke family fared better than other owners, in that many of their former slaves elected to continue working for them, they still needed new workers. With the support and assistance of the British and Dutch governments, they recruited large numbers of indentured labourers from India and Indonesia.

The descendants of those labourers and of the freed African slaves today contribute to Suriname's celebrated ethnic diversity. Indeed, given the social conditions in 19th century Suriname, some of those descendants may well also have Kirke blood running in their veins.

Around 1890 Robert Kirke bought the Nursery plantation. The three plantations (Waterloo, Hazard and Nursery) and the related sugar works at Waterloo remained in the control of the Kirke family until well into the 20th century. However, the Great Depression from 1929 and other factors brought difficult times for the sugar industry. The Nursery plantation had already closed by 1923, and Hazard followed in 1932.

Around the same time as Hazard closed, the Waterloo plantation and sugar works were sold to a company from Guyana (formerly British Guiana). Waterloo continued in business until 1969, when it too closed. Today almost nothing remains of the former Kirke empire. Many of the old Suriname plantations have reverted to bush.

Back in Burntisland, Robert Kirke was reinforcing his position as one of the town's leading citizens - but he was by no means universally popular. He may well be the only townsperson whose effigy was burned by a mob. This happened in 1880 when he obtained a court order to halt production at the Binnend Oil Works because of pollution in the burn running close to his Greenmount mansion. The Binnend employees and the local traders were enraged. The Town Council became involved at the suggestion of the court, but they were "rent in twain" as William Erskine colourfully noted in his "Glimpses of Modern Burntisland" (c1930). The issue was eventually resolved by the Council at their second attempt. They got the court order cancelled by promising to re-route the oil works' liquid waste into the town sewer.

The employees celebrated with a march from Binnend to the town centre, where Kirke's effigy was burned in the High Street, in front of the home of Thomas Wallace, the Town Clerk. Wallace was the target because he was Robert Kirke's son in law, although there is no evidence that he acted improperly. According to Erskine, this episode also opened up class differences in the town, with the supporters of the oil works being earmarked as dangerous radicals by the landed proprietors. Those radicals who were traders lost business as a result. William Erskine's distinction between the classes - dividing society into (a) the landowners and (b) everyone else - is rather different from how we see things today. Erskine himself was also closely involved in this issue, both as a radical member of the Town Council and as a prominent trader (watchmaker and jeweller in the High Street). He was later to prove a thorn in the flesh of the establishment as a close ally of James Lothian Mitchell.

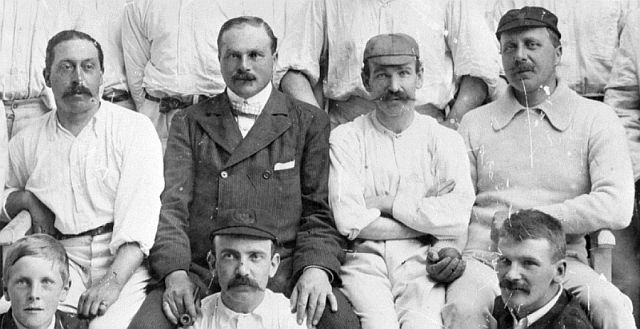

Burntisland Cricket Club

From a 1901 Burntisland Cricket Club photograph. Back row - on the left, James Johnstone of Kingswood (Captain); second from the left, John Johnstone Kirke (President); on the right, David James Balfour Kirke.

Erskine also recalled angry exchanges on the Burntisland Parochial Board, which administered the provisions of the Poor Law (Scotland) Act in Burntisland Parish. Robert Kirke was the dominant member of the Board, but he came under fire from new member Archibald Stocks for his "niggardly policy towards the out-door paupers ..... It was all very well for persons, he declared, like Mr Kirke, who rolled in wealth and luxury, to advocate a cheese-paring policy towards the poor in the name of economy; but let him try to live on the diet of the poor and he would view matters in a different light. Such an outbreak made Mr Kirke stare, and angrily resent the expressions used. His eyes would glare with rage and scorn, and his hand would grasp the knotted stick that was his companion and wave it as if he would strike, but Mr Stocks answered scorn with scorn. 'Keep your stick where it should be, and remember that you can't be a slave-driver here as if you were abroad.' "

According to tradition, Robert Kirke also exercised his feudal estate rights by insisting that new houses at Bentfield (those on the section of the south side of Kinghorn Road to the east of Lochies Road) be restricted in height so as not to spoil his view from Greenmount. Similar thinking may have prompted him to buy the foreshore, from the Beach Tearoom to Kingswood, in 1877.

However, there is evidence that Kirke could at times show a different face. In 1849 there was a slave rebellion on his Waterloo plantation. An official enquiry discovered that the rebellion had been caused by Kirke's appointment of a new manager (probably Gordon MacDonald) to run the plantation while he visited Scotland. The slaves objected to this change as Kirke was apparently "well-loved by the slave force".

He also gave support to old and infirm colleagues from Suriname. And in his will he left legacies, not just to the Erskine Church in Burntisland, but also to the congregation of the Moravian Church (pictured right) at Waterloo, Suriname, which he himself had built in 1870.

Lilian Neede Pickering of Paramaribo, Suriname, is a descendant of slaves who worked for the Kirkes. She has been researching the plantation families, and notes that: "The Kirke plantations flourished, when others in the country had big problems when the slaves were freed. That tells me that the Kirke slaves did not feel too bad at Waterloo."

However, Harold Rusland, a respected Suriname commentator and also a descendant of Kirke's slaves, adds a note of caution: "In 1870, problems with the laborers were lurking on the horizon, because the time of Government supervision was coming to an end. The solution of indentured British or East Indian laborers, had not been brought up yet. Did Kirke do all those things for the church because he wanted to influence his laborers positively through the church, in order to avoid problems?" When asked to assess Kirke, he commented: "We cannot compare him to others. We cannot say that he was bad or good; only that he did much for his slaves, later his laborers, and for the community."

By 1865 Robert and Janet Kirke had completed their family of eight children. However, their wealth and social status gave them no immunity to tragedy. In 1879 their youngest son, 14 year old William, died while in the care of the Scottish National Institution for the Education of Imbecile Children at Larbert. Their youngest daughter Jean died of tuberculosis in 1886 at the age of 22.

Kate, the eldest daughter, never married and seemed content to live off her allowance. She engaged in some charitable works, principally related to nursing, and she took an interest in local historical matters. Her golfing skills are not recorded, but from the booklet "200 Years of Golf in Burntisland" we learn that she had a key role at the opening of the course at Dodhead in 1892: "After speeches by local dignitaries, Miss Kirke of Greenmount, daughter of the proprietor of the ground, was asked to play off the first ball and a silver mounted club was presented to the lady, with which she drove off the ball amid much cheering."

Kate was elected to Burntisland School Board in 1906, although her candidature elicited the following assessment from a local commentator: "Miss Kirke's only way of dealing with a difficulty is to run away from it." She died of a stroke at Hilton, Kirkbank Road, in 1922. In her will she left £500 to the Burntisland District Nursing Association so that it could buy permanent premises of its own. The Association, which had been formed to help "the sick, the poor, and the working classes", bought the house at 6 Craigholm Crescent, which it used to further its work and also to provide a home for a District Nurse.

The second daughter Helen married Thomas Wallace, Town Clerk of Burntisland, and the third daughter, Janet, married Andrew Miller, a Glasgow minister.

The first and second sons, Robert (born in 1857) and John (born in 1859), became involved in the running of the plantations in Suriname and assumed complete control on the death of their father in 1894. They also established the firm of R. & J.J. Kirke, sugar merchants in London, which eventually became their main activity.

The third son, David, initially wanted to be a doctor, but changed his mind and became a London barrister instead. He maintained his Burntisland connections and in the early 1900s his home in the town was St Brendan in Cromwell Road. In 1901 he married Charlotte Shepherd, daughter of James Shepherd of Rossend Castle; and in the following year his brother John married Charlotte's sister, Una.

Unlike his father, David Kirke was popular in Burntisland. He served as Provost from 1912 to 1919, and he earned plaudits for his work in helping to bring major employers to the town - notably the shipyard and the aluminium works. He had also helped to secure the town's public library in 1907.

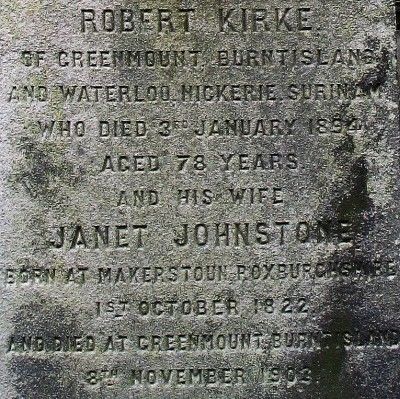

Robert Kirke's widow, Janet, died at Greenmount in 1903 following a stroke. From the Fifeshire Advertiser after her death: "Mrs Kirke was never ostentatious in her ways; she maintained the simplicity of her early years, and manifested the kindliness and gentleness which usually come from the long experience of the variations of human life."

Pictured right - detail from Robert and Janet Kirke's headstone in Cairneyhill Churchyard.

The terms of Robert Kirke's will had given his widow the use of Greenmount until she herself died in 1903 - but when Robert Kirke died in 1894 he had an overdraft of nearly £2m in today's terms, partly secured on Greenmount and other properties which had been valued at a total of the equivalent of £1.4m. Adam Johnstone, Robert Kirke's brother in law, had been aware in 1874 that Kirke could be facing financial difficulties. He made changes to his own will to give additional support to his sister (Kirke's wife) "in the event of the affairs of my brother-in-law Robert Kirk falling into disorder so that his family may be exposed to want".

When Janet Kirke died in 1903, the family tried to sell Greenmount, but despite a reduction in price a buyer could not be found. In stepped David Kirke, who probably felt some obligation to the old family home. He bought it from Robert Kirke's trustees (who included himself), and moved from the comfort of his Cromwell Road house to the draughty old mansion. There he remained until his death in 1927. Many years later, the late Stanley Robertson of Burntisland recalled his funeral: "I can remember the funeral of the late Provost Kirke. Was a bit overawed at the sight of the hearse and the horses with their plumes and the many, many cabs with the mourners."

David Kirke's widow, Charlotte, died in 1931 at Greenmount, and the house was again put up for sale. It remained unoccupied for some time, and was eventually bought and converted to the Greenmount Hotel, a venue which still holds fond memories for local people. It also served as an emergency hospital in the Second World War.

In June 1987 the Greenmount Hotel was destroyed by fire. It lay empty and derelict until April 2014, when it was demolished.

This article is a revised and updated version of the story of Robert Kirke which appears in "Burntisland: A Social History" by Iain Sommerville, published by Burntisland Heritage Trust.

Edit this text